Malaria: epidemiology, prevention and management of the disease

30 Sep 2025

Written by Jutta Marfurt

Overview

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease caused by the protozoan parasite of the genus Plasmodium. It remains one of the world’s most serious tropical diseases, with more than 250 million cases and around 600,000 deaths per year.

Malaria disease and epidemiology

There are over 150 known different Plasmodium species. Of these, four are considered true human parasites, as they use humans almost exclusively as their natural intermediate host (where the parasite grows, but not to its sexual maturity) and Anopheles (Figure 1) mosquitoes as their definitive host (where sexual reproduction occurs): P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae.

However, there are reports of simian malaria parasites being found in humans, most commonly P. knowlesi and P. cynomolgi. It remains unclear whether these species are being naturally transmitted from human to human via the mosquito vector, without their natural intermediate host (macaque monkeys of the genus Macaca). Therefore, P. knowlesi and P. cynomolgi are still considered zoonotic malaria (transmitted from animals to humans).

Figure 1: Anopheles mosquito vector. Scientists Against Malaria.

Transmission and life cycle

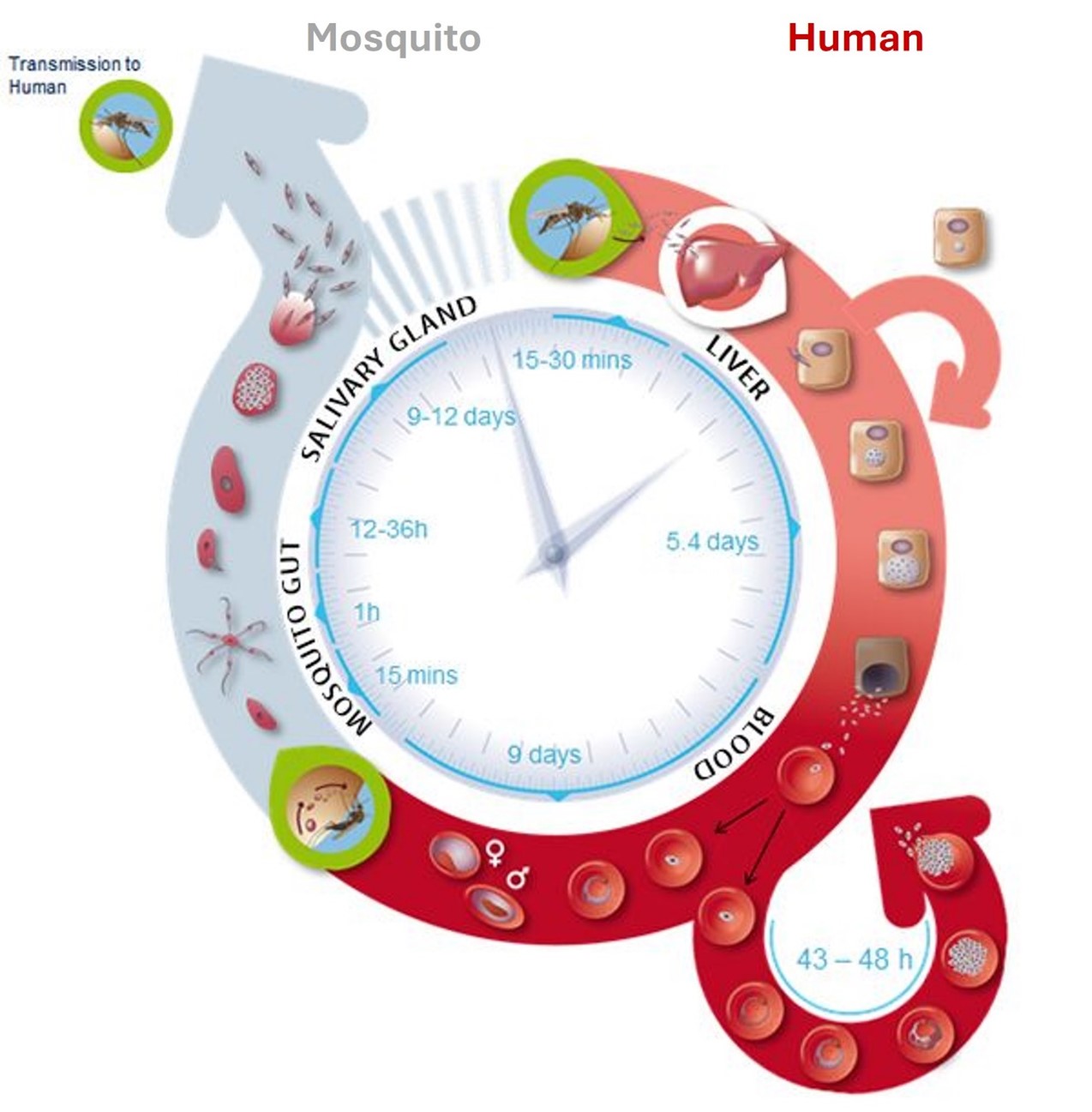

The malaria parasite reproduces sexually in the Anopheles mosquito vector and multiplies asexually in the human host during the erythrocytic cycle (blood-stage malaria) (Figure 2).

In contrast to P. falciparum, P. vivax parasites can form latent or dormant liver stages (hypnozoites) which, if not properly treated, can lead to recurring blood-stage infections.

Figure 2: The life cycle of human Plasmodium species. The Activities of Current Antimalarial Drugs on the Life Cycle Stages of Plasmodium: A Comparative Study with Human and Rodent Parasites.

Symptoms

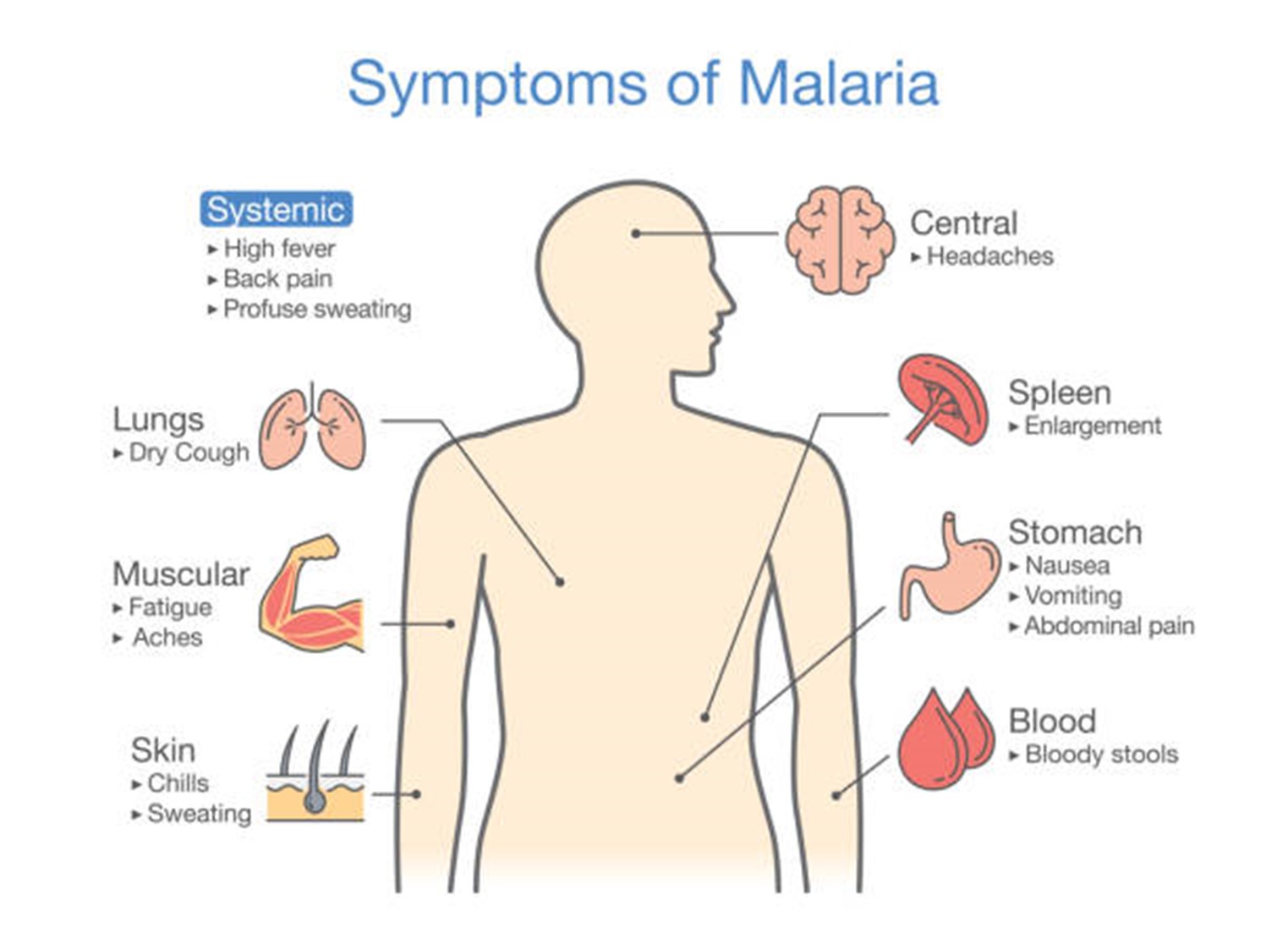

Human malaria causes flu-like symptoms, typically including headaches, fever, fatigue, vomiting and diarrhoea. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice (yellowing of the eyes and skin), seizures, coma, or death (Figure 3). Symptoms usually appear 7 - 15 days after being bitten by an infected Anopheles mosquito.

Figure 3: Symptoms of malaria. The Travel Doctor.

Distribution and impact of malaria species

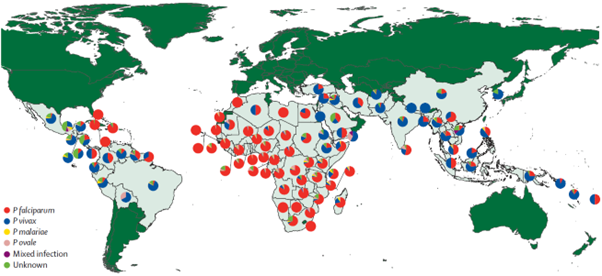

Although P. falciparum is the predominant malaria species in Africa, P. vivax malaria is equally prevalent in South America, Southeast Asia, and Oceania (Figure 4). While P. falciparum has long been regarded as the deadliest malaria species, studies over the past decades have shown that P. vivax contributes substantially to chronic malaria can lead to severe disease, too.

Figure 4: Relative Incidence of Plasmodium species by country of origin. The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Drug-resistant malaria in the region

The emergence and spread of drug-resistant Plasmodium parasites remain a major threat to disease control and elimination efforts. The Greater Mekong Subregion, which includes Cambodia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Myanmar, Thailand, Viet Nam, and China’s Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, has been the epicentre of the P. falciparum drug resistance. In this region, parasites have developed resistance to almost all antimalarial drugs used to date. Depending on the malaria drug resistance profile in each country, malaria treatment and chemoprophylaxis regimens (the use of drugs to prevent disease) have to be considered carefully and adapted accordingly.

Malaria prevention

Malaria prevention rests on four major pillars: awareness of risk, mosquito bite prevention, chemoprophylaxis, and prompt diagnosis and treatment in the event of an infection (Table 1).

| Component | Healthcare provider’s role |

|---|---|

| Awareness of risk | Ensure patients understand the risk of malaria and are informed about key symptoms and the potential timing of onset |

| Bite prevention | Provide guidance on mosquito bite prevention strategies (e.g. protective clothing, repellents, treated bed nets) |

| Chemoprophylaxis | Evaluate the need for chemoprophylaxis based on individual risk. If chemoprophylaxis is indicated, discuss options, appropriate dosing and potential side effects |

| Diagnose promptly and treat without delay | Advise patients to seek immediate medical attention for diagnosis and treatment if they develop a fever 1 week or more after entering a malaria-endemic area, particularly if exposure occurred within the past 3 months |

Table 1: Malaria strategies. The Australian College of Tropical Medicine.

Current Australian treatment guidelines and recommended drug regimens for malaria chemoprophylaxis are summarised in Table 2. The choice of the regimen depends on factors such as travel destination, duration of travel, potential side effects, drug interactions, cost and convenience.

Table 2: Choosing Chemoprophylactic Medication. The Australian College of Tropical Medicine.

Diagnosis and treatment of malaria

Malaria symptoms are non-specific in nature; therefore, diagnosis is usually first suspected based on symptoms and travel history, and then confirmed with a laboratory test to detect the presence of the parasite in the blood (parasitological test).

Diagnosis

Malaria is often confirmed by the microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained blood films or by rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) that detect parasite antigens. Since microscopic examination of blood films requires highly skilled personnel, RDTs are used in settings where this expertise is not available. However, microscopy remains the gold standard test for malaria diagnosis. Where available, initial microscopic diagnosis can be further confirmed by using tests that detect the parasite DNA (nucleic acid amplification tests).

Treatment

Malaria is treated with prescription medication to kill the parasite. The choice of the regimen depends on:

- the infecting Plasmodium species

- the geographic area where infection was acquired

- the clinical status of the patient (severity of symptoms)

- the age of the patient

- medication safety such as contraindications or potential allergic reactions against an antimalarial drug.

Malaria is treated with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT), which combines 2 or more drugs that work against the malaria parasite in different ways. Examples include artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem) and artesunate-mefloquine (ASMQ FDC).

Radical cure (eliminating of dormant liver stage parasites) of P. vivax malaria requires an additional course of an 8-aminoquinoline antimalaria such as primaquine (brands include Jasoprim, Malirid, Primacin) or tafenoquine (Arakoda, Krintafel).

Important pre- and post-deployment travel considerations

Before embarking on overseas work travel or an AUSMAT deployment, it is advised that travellers undergo a pre-travel risk-assessment which includes information on malaria, where relevant.

When conducting a risk assessment and providing advice for malaria, the following should be considered:

- Malaria epidemiology at travel destinations(s): Determine whether the traveller is visiting malaria-endemic areas and assess the level of risk.

- Risk of exposure and disease severity: Conduct an individualised assessment of the traveller’s fitness to travel, planned or possible itinerary, activities during the trip, willingness to use personal protective measures, and individual factors that may influence exposure risk, disease severity and practicality of recommendations.

- Optimal malaria prevention approach: Consider general preventative measures such as protective clothing, mosquito repellents and insecticide-treated bed nets. Identify the most suitable prevention strategy based on an individual assessment of risk and the traveller’s preferences in terms of prophylaxis.

- Diagnosis and treatment in the event of illness: Educate the traveller on the importance of seeking medical attention promptly if they become unwell during their journey or after returning to Australia.

References

- mAntinori S, Milazzo L, Ridolfo AL, Galimberti L, Corbellino M. 2012. Severe Plasmodium vivax: fact or fiction? Clinical infectious diseases 55(11):1581-3. doi: 1093/cid/cis709. Epub 2012 Aug 21. Erratum in: Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Apr;56(8):1196. PMID: 22911647.

- Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum 2009. The New England journal of medicine 361(5):455-67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859

- Artemisinin-Resistant alaria in Asia. 2009. The New England journal of medicine 361(5):540-1. doi: 1056/NEJMc0900231.

- Ashley EA, Pyae Phyo A, Woodrow CJ. 2018. Malaria. The Lancet 391 (10130): 1608–1621. doi:1016/S0140-6736(18)30324-6.

- Batchelor T, Gherardin, T. 2007. Prevention of malaria in travellers. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

- Delves M, Plouffe D, Scheurer C, Meister S, Wittlin S, et al. 2012. The Activities of Current Antimalarial Drugs on the Life Cycle Stages of Plasmodium: A Comparative Study with Human and Rodent Parasites. PLOS Medicine 9(2): e1001169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001169.

- Mueller I, Galinski MR, Baird JK, Carlton JM, Kochar DK, et al. 2009. Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect Disease 9 (9):555-66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X.

- Price RN, Tjitra, E, Guerra, CA, Yeung, S, White NJ, Anstey, NM. 2007. Vivax Malaria: Neglected and Not Benign. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 77(6 Suppl):79-87. doi:4269/ajtmh.2007.77.79

- Scientists Against Malaria. 2025. Anopheles, the Vector.

- Tatem AJ, Jia P, Ordanovich D, Falkner M, Huang Z, et al. 2017. The geography of imported malaria to non-endemic countries: a meta-analysis of nationally reported statistics. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 17 (1): 98–107. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30326-7. Epub 2016 Oct 21. PMID: 27777030; PMCID: PMC5392593.

- The Australian College of Tropical Medicine. 2022. Malaria Prevention Guideline.

- The Travel Doctor. 2023. Malaria Information for Travellers: Know This Before Leaving Home.

- Wongsrichanalai C, Pickard AL, Wernsdorfer WH, Meshnick SR. 2002. Epidemiology of drug-resistant malaria. The Lancet Infect Diseases 2(4):209-18. doi: 1016/s1473-3099(02)00239-6. PMID: 11937421.

- World Health Organization. 2015. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria.

- World Health Organization. 2024. World Malaria Report.